Briefing Summary

- Interest rate increases have created a domino effect in the market for startups and established businesses, making money more expensive to lend & borrow

- With fundraising rounds less frequent and credit lines more expensive, companies will be increasingly cash conscious and focused on profitable revenue

- Sellers need to adapt new tactics for this era where CFOs have more weight than ever before

- Product-focused messaging will fail, automation is not a cure-all, and being blaisé about your own numbers is a surefire way to get caught flat footed

- Sellers need to be focus on workflows, fish for deals like a spear fisher, and be disciplined about their own numbers

The end of easy money

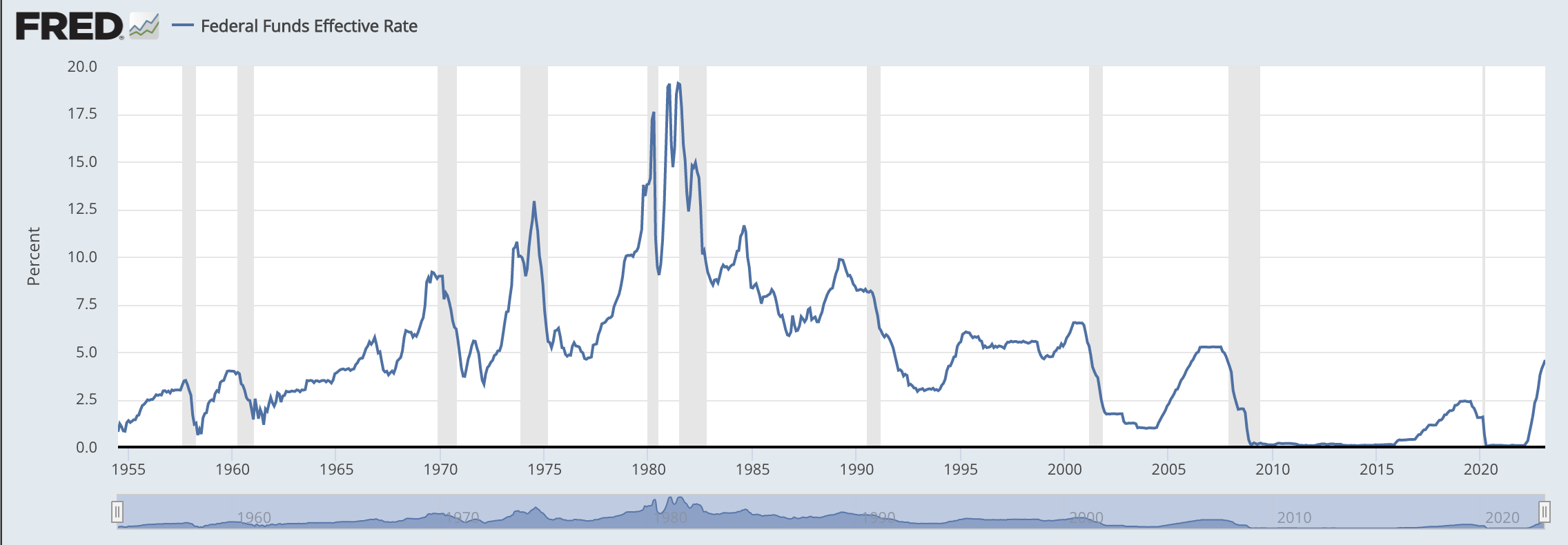

Since the early 1980s, interest rates have been trending downward. It's seemed like a law of physics that interest rates would gradually go lower and lower. This was not always the case – as you can see from this historic chart between 1955 and today.

Consider if you had a billion dollars. (I mean... one can dream) The safest bet to preserve those billion dollars is to buy a bond, usually from the US government. You're loaning money to the government and they promise to pay you back at some date in the future.

The problem is starting in 2008, bonds would offer you, uh, basically nothing in return. That's the interest rate. (See chart above) So you could buy a bunch of bonds and preserve your pool of cash, but if you're a pension fund or a big institutional investor, you need the pool of cash to grow every year.

So you dedicate a big chunk of money into venture capital funds to make extremely risky bets on startups – most of whom fail. But if you invested in the fund that creates Uber, Airbnb, and so on, you get a huge payout compared to your bonds.

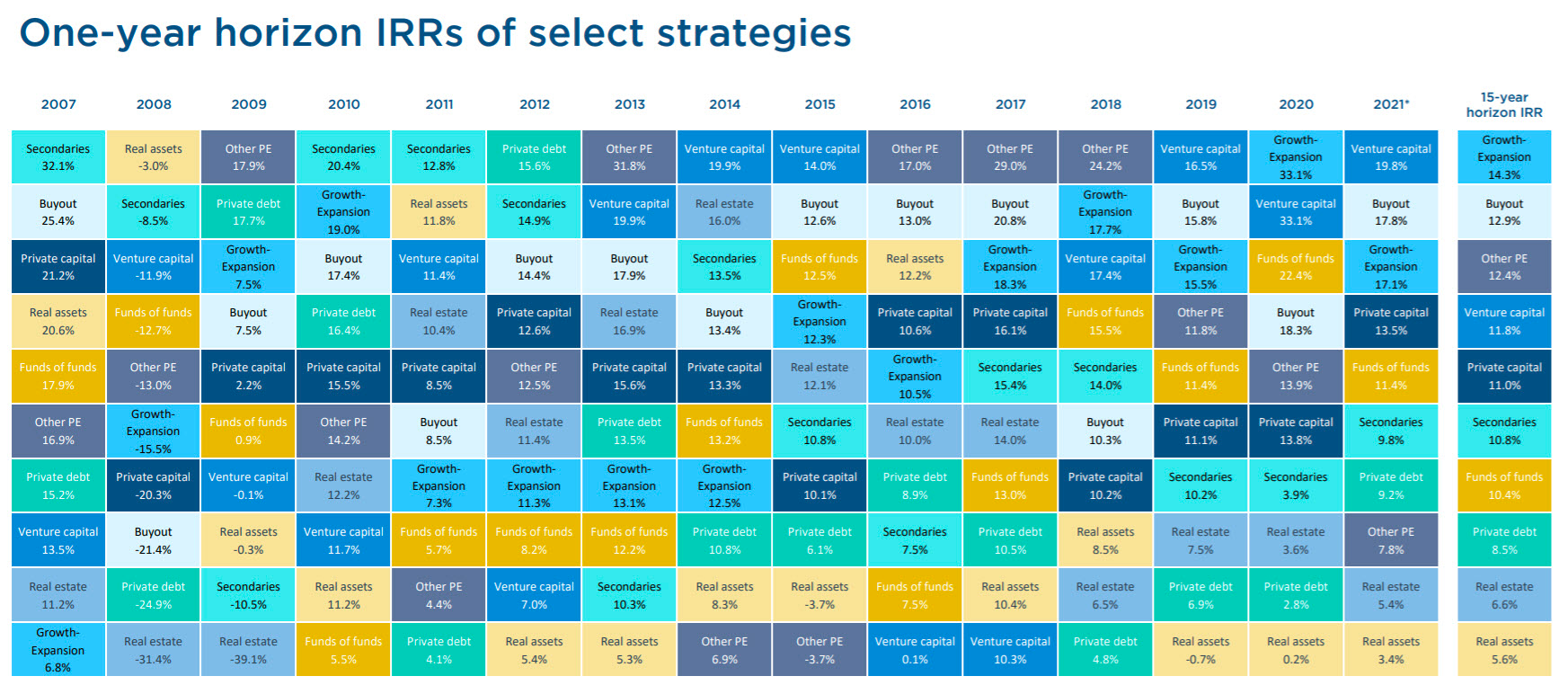

Consider in 2021: the average internal rate of return (IRR) for venture capital was 19.8%. That is much much higher than a 2% US Treasury bond. But like all risky strategies – that's an average for one year. (If you can find it, check the VC return in 2009 or 2016). Many funds will earn very little in a given year, and many will earn well above that average.

But now interest rates are increasing. Bonds are now worth something – and they're a much safer bet than those risky VC funds.The Fed continues to increase interest rates, making these bonds all the more attractive.

Companies and large institutional investors can earn 5% on a bond, risk-free. (Think about that – can your software generate a 5% return for the company??) But anyway, this has created a domino effect in the market:

- Big institutional investors will pull money from riskier bets (like stocks) and put them in safe bets (like bonds), causing the price of stocks to fall as they sell them off.

- Therefore, the likelihood of a big IPO for a startup drops as well. A startup that goes public won't be worth as much if Facebook or Microsoft is also worth less.

- Venture capitalists will demand a better deal from startups. They need to recuperate their money more effectively. The size of a round will shrink.

- Additionally, institutional investors will tell venture capital funds to not come back for more money as they're more likely to invest in safer assets as interest rates rise.

- Venture capitalists then can't spend money as quickly because they won't be able to get their next raise. The pace of deals will slow.

The Economist in January:

Venture capitalists are listening. Harry Nelis, a partner at Accel, a venture-capital firm, speculates that cash which might have taken a year to spend during the market boom will now be made to last around three time as long.

Whoa. Startup land is really taking a toll as a result. VC funds slowing to 1/3 of their previous pace impacts deals of sizes and all stages.

The credit problem for business

One benefit of being a startup raising a $100 million round of investment is that it is cash in your bank account you can burn through over a period of years. But most business doesn't work this way.

Most business relies on credit. Credit is effectively a loan. It can be credit cards, a revolving credit line you draw down and periodically repay, or even corporate bonds for the big companies – where you sell a corporate to the market and eventually pay them back at a set interest rate. But credit gives you buying power. The loan gives you cash on hand you can use to hire, invest, and spend.

The price of credit is interest. Interest is what you pay back to your creditors as the price of doing business. They loaned you $1MM dollars with a 10% interest rate, they get a 10% return ($1.1MM total).

As interest rates go up, credit becomes more expensive. A mortgage for a house at 2% is a lot less per month than a 7% mortgage. Same goes for businesses.

Businesses who have debt think a lot about liquidity, essentially their cash on hand to pay back debts. Consider a business that is worth $100 million, but $80 million of it is tied up in manufacturing equipment and big buildings. Those are "illiquid" investments – it'd take a long time to sell the equipment and buildings, and turn their investments into cash.

So most business executives think a lot about this puzzle – how much revenue needs to be generated, how much operating income they have, how much debt they owe and what it costs to pay back that debt, and so on. The economics of the firm is a huge chunk of most MBA curriculum.

But what happens when interest rates are 0%? When it's easy and cheap to borrow money – and for years and years the interest rate is 0% or very close to 0% – you don't have to think about this puzzle too hard. Even if you're running out of cash, you can always get more money, right?

...Right? 😳

Think about the number of unprofitable businesses with high cost of acquisition, high customer churn, and no opportunity to truly expand in the market beyond some minor software niche. During an era of easy money, they'd get grouped into all the other businesses getting cheap credit or a large fundraising round since there was just so much money. But now, these models are running into the brick wall of reality.

The new environment of financial discipline

With changing interest rates, we're starting to herald a new environment of financial discipline that hasn't been around for quite some time. Now that you've got the basics of the puzzle... what does this all mean?

- Increasing interest rates means borrowing money for expansion is more expensive and startups will have a harder time raising investment

- Companies across the board will be more cash conscious and will seek to cut costs, delay projects, and slow hiring

- Large companies will be more strategic in their acquisitions since most (outside of the top Fortune 50) don't have the cash on hand to purchase startups, meaning they'll need to borrow to pay for it

- Startups will need to be more disciplined about their revenue growth in order to appease future investors or acquirers

- Companies will need to be more disciplined about their profit growth in order to appease public markets or private investors

Selling in this environment requires a different tact than in an era of easy money. There are three things I'm thinking about.

1/ Your product won't cut it anymore. Think critically about workflow problems.

A lot of marketing + sales has focused on how great the product is in B2B. When cash was flying free, everyone could buy & sell on the basis of what the product does alone. It was cool, fun, fancy, AI-powered, whatever.

Startups and companies will struggle bridging the "nice to have" to "need to have" gap in an era of cash consciousness. When we talk about mapping the earthquake, it's about identifying the person who's most impacted by the purchasing decision. What workflow is currently broken that your product solves? What day-to-day pain does this person experience?

Usually that person is not a senior decision-maker, so it's our job to do the research and surface these problems to senior decision-makers. Help them understand the financial cost of these broken workflows to the company & how fixing them will help solve core financial challenges to the company.

2/ Automation won't solve your sales challenges.

In the rush to cut costs, I can imagine a well-meaning sales manager or sales director pushing for more more more via automation. After all, automation helps us be more efficient. We need to cast a wide net and find those who will bite, right?

Wrong. In episode #56, I talked about spear fishing vs. net fishing:

Spear fishers always hit the fish. And the reason is they patiently study the movements of the fish in the water – otherwise known as studying the pain of their target customers in the market. What this leads to is an entire shift in thinking about activity metrics, because what Nick had pointed out is – does it really matter if you prospect 30 hours a week, if you only hit a fish 20% of the time? Not really.

Hitting quota and revenue targets requires a more focused approach to targeting, messaging, and reaching prospects. Automation only enhances what's already in place. If you have a sales process that doesn't convert a lot of leads, automation will just do...more of not-converting-a-lot-of-leads.

The truth is: if you can't do it manually, you won't be able to do it automatically. Getting back to basics – knowing the pains & problems you solve, who you solve it for, why it matters, and why inaction is much more expensive than choosing to work with you – will be the key determinant to opening (and closing) qualified opportunities in this environment.

3/ Hitting quota is about staying in control of your own numbers.

Going to sidestep overly ambitious quotas for a moment – those companies are in for a world of hurt right now anyway, since so many have relied on the easy money environment to grow an unprofitable business model.

Knowing your numbers is absolutely key to staying on top of quota in this environment. If you're an AE, that will usually be a total $ amount of closed-won deals. SDR/BDRs, you might have more variability: it could be total meetings booked, total # of qualified opportunities, $ in pipeline influenced, and so on.

But consider for a moment you have a $1MM quota and your average deal size is $100K. That means you need 10 deals to close. What's your opportunity-to-close ratio? It should be 20% or higher. So at a 20% close rate, you need 50 deals in pipeline to hit quota.

So what will it take for you to generate 50 deals in pipeline? And what will it take for you to manage 50 deals in pipeline? Staying on top of your numbers is the only way to stay in the driver's seat in this new era of financial discipline.